Smalti

- Filati Technique

Written by Rochelle, April 2011

Smalti

Smalti is a type of glass paste,

(sometimes it is translated as enamel), that was developed centuries

ago to enhance, and then ultimately take precedence over colored marble in

mosaics.

Today, the dominant producers of smalti are all family owned businesses:

Orsoni (Venice, Italy), Dona (Murano & Spilambergo, Italy), and Perdomo

(Cuernavaca, Mexico).

It is hand made in small batches, each color poured and cooled in small

puddles, about 3/16” -1/4” in thickness.

In Italy they call these puddles of smalti “pizzas”. In Mexico, they are

called, not surprisingly, tortillas.

The Italian smalti is thicker, and is turned on its side where the richness

of the colors can be fully revealed.

Due to the air bubbles that naturally occur in Italian smalti, and also due

to tradition, one does not grout works made in Italian smalti as it settles

into the bubble holes and creates a horribly ugly surface – think bad skin

disease!

Mexican smalti can be used on its side or with either the top or bottom

surface facing up.

Mexican smalti, lacking the air bubbles that Italian version has, can be

grouted.

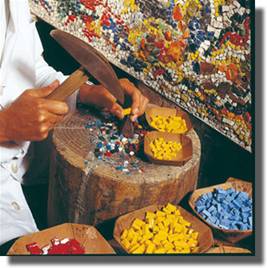

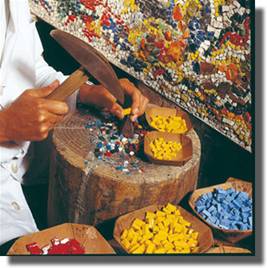

Cutting Smalti

Traditionally, smalti is cut

using a “hammer” and a “hardie”.

This tradition goes back to at least the 2nd century Roman era

(there is a bas relief sculpture showing artisans using these same tools).

|

As mentioned earlier, smalti slowly took over the tradition of using colored

marble in mosaics.

Smalti, being more of a glass paste, is not as brittle as the glass most

people today are familiar with.

Therefore, as the mosaic materials changed from marble to smalti, the

method and tools of cutting tessare did not change, and thus a complete

re-tooling of the ancient mosaic industry was averted.

Henry Ford himself would have been impressed!

In my micro mosaics that are not

made with filati, I use the hammer and hardie to cut my class.

Filati

Filati is typically made from smalti, rather than other glass.

It is different from other rods in that, again, it is handmade, with each

pull resulting in a unique color, never repeated.

The artist can customize the filati as she/he sees fit.

Traditionally, filati was made to create micro-mosaics.

The Vatican took a keen interest in the development of filati to replace

all of the paintings, save one,

in the nave of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome (the heat and humidity began to

rot the masterpiece paintings, all of which were replaced by exact replicas

in micro mosaic that are so perfect, most visitors fail to realize they are

looking at mosaics rather than paintings).

As the fashionable and polite society of the mid-1600’s through the

mid-1800’s sent their “20 somethings” on a Grand European Tour, the demand

for souvenirs (micro mosaic jewelry and snuff boxes being the most popular),

grew immensely. In the earlier days, one would create an image using single

colored filati, typically in a simple lozenge shape, to painstakingly create

delicate and elaborate imagery on a very small scale.

Usually the images were based on tourist sites, for instance the Coliseum.

As the demand for these increased, methods were developed to speed up the

production.

Still all handmade and pulled, artisans began using what in Italian is

called “malmisticato” – or “badly mixed”.

This approach would blend more than one color together, creating a marbled

effect in each rod.

And, in addition to the small lozenge shapes, filati would be made into

circular, square, rectangular, tear drop, leaf

and c-shapes.

Again, as the desire for more realistic and exquisite imagery increased,

artists could now use, for instance, a malmisticato filato in the shape of

the letter “c” and use it to mimic the hair of a person or the fur of dog –

one piece of glass rather than the 10 or so pieces it used to require.

Traditionally, the filati would be between 1 and 3 mm in size. In my work,

I tend to stretch the limits of size – at times going as small as a thread.

Also, traditionally once the filati have all been set and the adhesive

dried, the micro mosaic would be ground down to create a very smooth

surface. In my work, I prefer the rough edges which reflect and refract

light in such a delightful manner that I cannot imagine grinding that all

away!

Adhesives and Supports

The traditional adhesive used in

ancient mosaics was a mixture very much like our modern cement. As mosaics

became more refined, they required smaller tessare, and therefore an

adhesive that wasn’t as clumsy as cement. For micro mosaics, artisans would

create a “stucco” from powdered marble, lime, and linseed oil. They would

blend, and knead these ingredients into a paste, and then store it in a

wooden box for 1-10 years (!!), until it was fully dry. Then they would

chip out a chunk, grind it down and add linseed oil to create the perfect

consistency for the filati to be supported. Needless to say, ancient and

Romantic timelines are very different from our modern demands! Usually I

use window putty to place my filati in – it is remarkably similar to the

texture and consistency as the traditional stucco. This time-saving “trick”

was passed on to me from the masters in Italy working in micro mosaic where

I was trained.

Traditional supports for filati

were shallow boxes made of marble, granite, ceramic, glass or fine metals.

Today, many micro-mosaics use a wooden or metal support. I use wood or

silver.

In the mosaics where I did not

use filati, my supports are wood, painted black. The adhesive is clear

silicone.

|